Storage Model¶

Overview¶

The figure below represents the fundamental abstractions of the DAOS storage model.

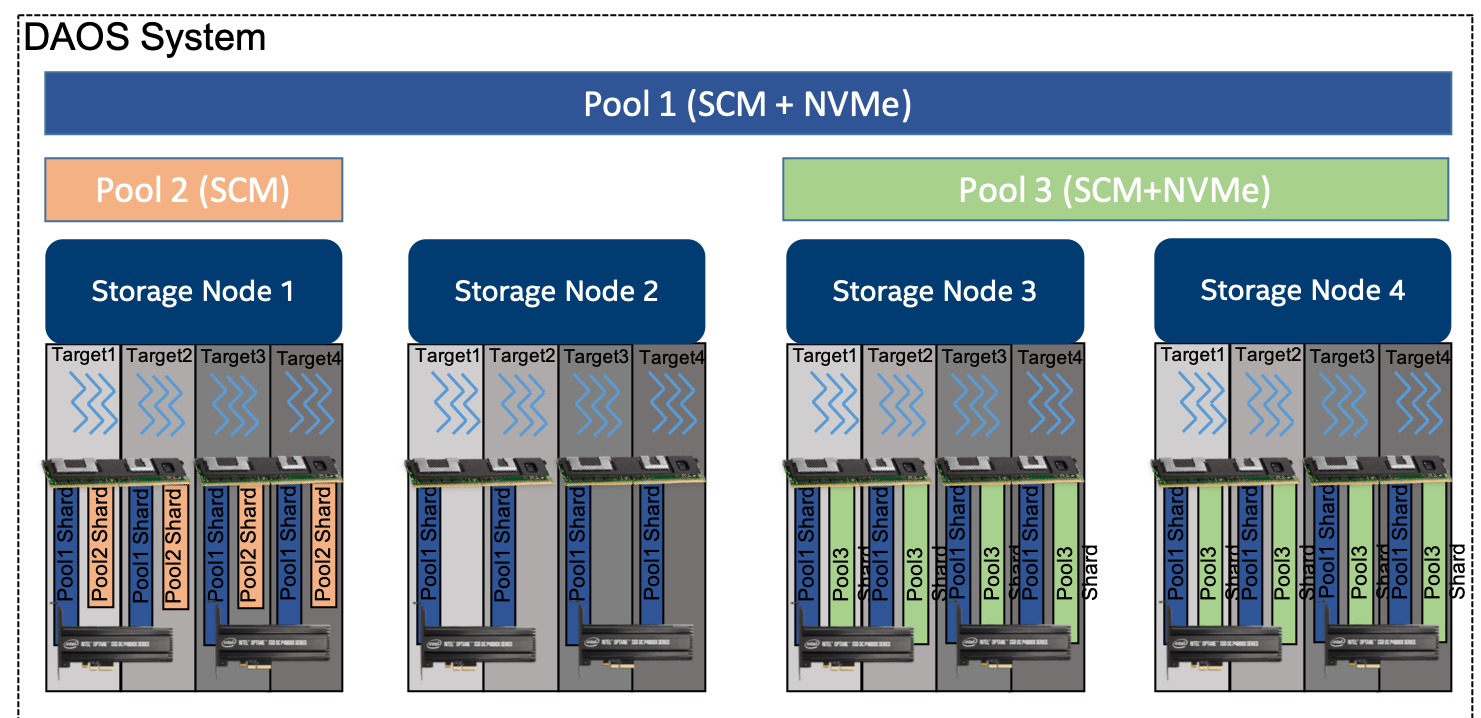

A DAOS pool is a storage reservation distributed across a collection of targets. The actual space allocated to the pool on each target is called a pool shard. The total space allocated to a pool is decided at creation time. It can be expanded over time by resizing all the pool shards (within the limit of the storage capacity dedicated to each target), or by spanning more targets (adding more pool shards). A pool offers storage virtualization and is the unit of provisioning and isolation. DAOS pools cannot span across multiple systems.

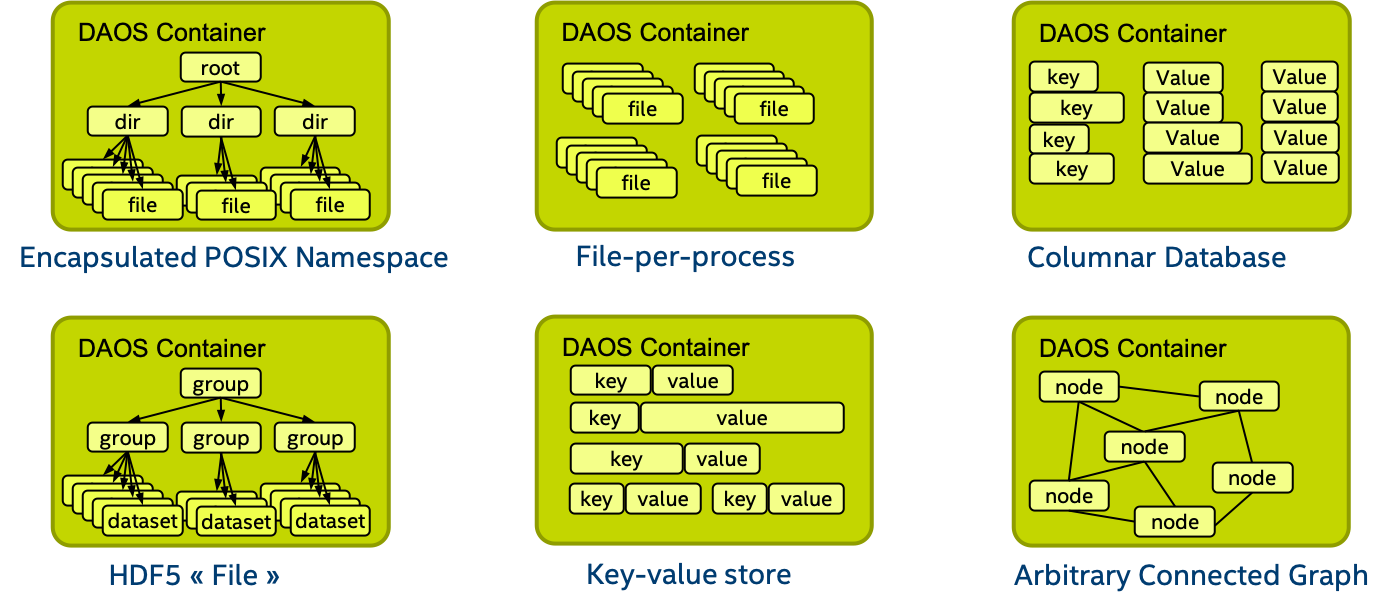

A pool can host multiple transactional object stores called DAOS containers. Each container is a private object address space, which can be modified transactionally and independently of the other containers stored in the same pool. A container is the unit of snapshot and data management. DAOS objects belonging to a container can be distributed across any target of the pool for both performance and resilience and can be accessed through different APIs to represent structured, semi-structured and unstructured data efficiently

The table below shows the targeted level of scalability for each DAOS concept.

| DAOS Concept | Scalability (Order of Magnitude) |

|---|---|

| System | 105 Servers (hundreds of thousands) and 102 Pools (hundreds) |

| Server | 101 Targets (tens) |

| Pool | 102 Containers (hundreds) |

| Container | 109 Objects (billions) |

DAOS Pool¶

A pool is identified by a unique pool UUID and maintains target memberships in a persistent versioned list called the pool map. The membership is definitive and consistent, and membership changes are sequentially numbered. The pool map not only records the list of active targets, it also contains the storage topology in the form of a tree that is used to identify targets sharing common hardware components. For instance, the first level of the tree can represent targets sharing the same motherboard, and then the second level can represent all motherboards sharing the same rack and finally the third level can represent all racks in the same cage. This framework effectively represents hierarchical fault domains, which are then used to avoid placing redundant data on targets subject to correlated failures. At any point in time, new targets can be added to the pool map, and failed targets can be excluded. Moreover, the pool map is fully versioned, which effectively assigns a unique sequence to each modification of the map, particularly for failed node removal.

A pool shard is a reservation of persistent memory optionally combined with a pre-allocated space on NVMe storage on a specific target. It has a fixed capacity and fails operations when full. Current space usage can be queried at any time and reports the total amount of bytes used by any data type stored in the pool shard.

Upon target failure and exclusion from the pool map, data redundancy inside the pool is automatically restored online. This self-healing process is known as rebuild. Rebuild progress is recorded regularly in special logs in the pool stored in persistent memory to address cascading failures. When new targets are added, data is automatically migrated to the newly added targets to redistribute space usage equally among all the members. This process is known as space rebalancing and uses dedicated persistent logs as well to support interruption and restart. A pool is a set of targets spread across different storage nodes over which data and metadata are distributed to achieve horizontal scalability, and replicated or erasure-coded to ensure durability and availability.

When creating a pool, a set of system properties must be defined to configure the different features supported by the pool. Also, users can define their attributes that will be stored persistently.

A pool is only accessible to authenticated and authorized applications. Multiple security frameworks could be supported, from NFSv4 access control lists to third party-based authentication (such as Kerberos). Security is enforced when connecting to the pool. Upon successful connection to the pool, a connection context is returned to the application process.

As detailed previously, a pool stores many different sorts of persistent metadata, such as the pool map, authentication and authorization information, user attributes, properties, and rebuild logs. Such metadata is critical and requires the highest level of resiliency. Therefore, the pool metadata is replicated on a few nodes from distinct high-level fault domains. For very large configurations with hundreds of thousands of storage nodes, only a very small fraction of those nodes (in the order of tens) run the pool metadata service. With a limited number of storage nodes, DAOS can afford to rely on a consensus algorithm to reach agreement, to guarantee consistency in the presence of faults, and to avoid the split-brain syndrome.

To access a pool, a user process should connect to this pool and pass the

security checks. Once granted, a pool connection can be shared

(via local2global() and global2local() operations) with any or all of its

peer application processes (similar to the openg() POSIX extension).

This collective connect mechanism helps to avoid metadata request storm

when a massively distributed job is run on the datacenter.

A pool connection is revoked when the original process that issued

the connection request disconnects from the pool.

DAOS Container¶

A container represents an object address space inside a pool and is identified by a container UUID. The diagram below represents how the user (I/O middleware, domain-specific data format, big data or AI framework, ...) could use the container concept to store related datasets.

Like pools, containers can store user attributes. A set of properties must be passed at container creation time to configure different features like checksums.

To access a container, an application must first connect to the pool and then open the container. If the application is authorized to access the container, a container handle is returned. This includes capabilities that authorize any process in the application to access the container and its contents. The opening process may share this handle with any or all of its peers. Their capabilities are revoked on container close.

Objects in a container may have different schemas for data distribution and redundancy over targets. Dynamic or static striping, replication, or erasure code are some parameters required to define the object schema. The object class defines common schema attributes for a set of objects. Each object class is assigned a unique identifier and is associated with a given schema at the pool level. A new object class can be defined at any time with a configurable schema, which is then immutable after creation (or at least until all objects belonging to the class have been destroyed). For convenience, several object classes that are expected to be the most commonly used will be predefined by default when the pool is created, as shown in the table below.

Sample of Pre-defined Object Classes

| Object Class (RW = read/write, RM = read-mostly | Redundancy | Layout (SC = stripe count, RC = replica count, PC = parity count, TGT = target |

|---|---|---|

| Small size & RW | Replication | static SCxRC, e.g. 1x4 |

| Small size & RM | Erasure code | static SC+PC, e.g. 4+2 |

| Large size & RW | Replication | static SCxRC over max #targets) |

| Large size & RM | Erasure code | static SCx(SC+PC) w/ max #TGT) |

| Unknown size & RW | Replication | SCxRC, e.g. 1x4 initially and grows |

| Unknown size & RM | Erasure code | SC+PC, e.g. 4+2 initially and grows |

As shown below, each object is identified in the container by a unique 128-bit object address. The high 32 bits of the object address is reserved for DAOS to encode internal metadata such as the object class. The remaining 96 bits are managed by the user and should be unique inside the container. Those bits can be used by upper layers of the stack to encode their metadata, as long as unicity is guaranteed. A per-container 64-bit scalable object ID allocator is provided in the DAOS API. The object ID to be stored by the application is the full 128-bit address, which is for single use only and can be associated with only a single object schema.

DAOS Object ID Structure

<---------------------------------- 128 bits ----------------------------------> -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |DAOS Internal Bits| Unique User Bits | -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- <---- 32 bits ----><------------------------- 96 bits ------------------------->

A container is the basic unit of transaction and versioning. All object operations are implicitly tagged by the DAOS library with a timestamp called an epoch. The DAOS transaction API allows to combine multiple object updates into a single atomic transaction, with multi-version concurrency control based on epoch ordering. All the versioned updates may be periodically aggregated, to reclaim space utilized by overlapping writes and to reduce metadata complexity. A snapshot is a permanent reference that can be placed on a specific epoch to prevent aggregation.

Container metadata (list of snapshots, container open handles, object class, user attributes, properties, and others) are stored in persistent memory and maintained by a dedicated container metadata service that either uses the same replicated engine as the parent metadata pool service, or has its own engine. This is configurable when creating a container.

Like a pool, access to a container is controlled by the container handle.

To acquire a valid handle, an application process must open the container

and pass the security checks. This container handle may then be shared with

other peer application processes via the container local2global() and

global2local() operations.

DAOS Object¶

To avoid scaling problems and overhead common to a traditional storage system, DAOS objects are intentionally simple. No default object metadata beyond the type and schema is provided. This means that the system does not maintain time, size, owner, permissions or even track openers. To achieve high availability and horizontal scalability, many object schemas (replication/erasure code, static/dynamic striping, and others) are provided. The schema framework is flexible and easily expandable to allow for new custom schema types in the future. The layout is generated algorithmically on object open from the object identifier and the pool map. End-to-end integrity is assured by protecting object data with checksums during network transfer and storage.

A DAOS object can be accessed through different APIs:

-

Multi-level key-array API is the native object interface with locality feature. The key is split into a distribution (dkey) and an attribute (akey) key. Both the dkey and akey can be of variable length and type (a string, an integer or even a complex data structure). All entries under the same dkey are guaranteed to be collocated on the same target. The value associated with akey can be either a single variable-length value that cannot be partially overwritten, or an array of fixed-length values. Both the akeys and dkeys support enumeration.

-

Key-value API provides a simple key and variable-length value interface. It supports the traditional put, get, remove and list operations.

-

Array API implements a one-dimensional array of fixed-size elements addressed by a 64-bit offset. A DAOS array supports arbitrary extent read, write and punch operations.